Fighters of the winter along the road at Avize.

Fighters of the winter along the road at Avize.We are in the middle of February, and a funny phenomenon has emerged on some of the plots along the highway between Louvois and Vertus. Little oil lamps - about half the heigth of the fence - has been put up with only a few metres between them up and down the rows.

They are not lit. So far they just stand there as an ominous mystery army of metal, but they are not. Not at all. On the contrary they are entrepreneurial winegrowers weapon against the first enemy of the year. The cold and icy hand of King Winter.

Frost in spring is the enemyChampagne is geographically so Northern, that the area is just around the limits of where you can grow wine on a major professional scale. Here is just about the necessary amount of hours with sunshine to mature the grapes. But also cold winters with risk of frost in the night as late as april.

Snow in Côte des Blancs.

Snow in Côte des Blancs.During the coldest months of winter the wine protects itself. Its growth has stopped, and while it hibernates, the plant is protected by its hardened branches and its concentrated latex, that has a much lower freezing point than the normal and more watery juice. Also part of choosing the right variety of wine for the area is to take the cold winters into account. In Champagne all three grape varieties - Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir - will stand frost at least 15 degrees Celsius below zero. With even stronger frost the vine may simply fracture, but that is very rare.

Much more serious and unfortunately also more common is the frost in spring. More or less one year out of three, it causes problems, big or small. The critical time is when the buds open around March-April. Only when they are two days old they can stand temperatures lower then zero. This means, that frost in the period inbetween is a bit of a kiss of death, that may destroy any imaginable percentage of the potential crop. The buds are burned, the winegrowers say. On top of the poorer harvest add that frost in general weakens the wineplants.

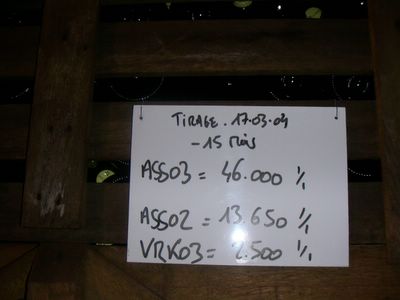

Now the winegrowers are allowed to keep a certain amount of litres of wine per hectare as a reserve. In some cases this can be used if the harvest fails, which means that a bad year due to for instance frost does not necessarily mean a smaller production. Before this system of stocks was introduced inventive solutions like the little lanterns in Avize have been used to help the tender buds keeping warm in a critical period.

Little lamps and small windmillsThe coldest wineyards are the lower ones; cold air sink, and since the frost is more severe at the level of the soils, the lower fields are more exposed to damages.

The windmills at Avize are to put the cold air in motion.

The windmills at Avize are to put the cold air in motion.Especially the most Southern area in Champagne - the Côte des Bar - is in the risky zone of frost. But also Avize and le Mesnil - two Grand Cru villages of the Côte de Blancs - are exposed, because part of their wineyards lie in a both low and flat area. And this is excactly the place where we at the spot of the lamps but on the other side of the highway see a chain of windmills with the same mission.

The mills are little buildings, several metres tall, brick-built and with 20-30 metres between them. When their electric airscrews are rotating, they set the air in motion, whip the cold air in the artificially made turbulence upwards and away from the plants. Just the fact that someone actually found such a rather fundamental solution suitable, gives an idea about how important it was and still is in some places to fight the frost.

The lamps burn with the help of paraffin, oil or gas. Some of them are so advanced, that they if critical temperatures occur ignites themselves. Rather nice, especially at night, where your main alternative is to park your car in the outskirts of the wine and spend the night there. This enables you to get out regularly to check the temperatures. And this is not just a sort of romantic memories from the days that were.

The cheap homemade solution is oil in a can.

The cheap homemade solution is oil in a can.A close friend of our family whose wine grow in le Mesnil between Avize and Vertus enjoys his retirement not any longer getting up to light little lampers in the middle of dark and freezing winternights. An old uncle never used neither lamps nor anything else: These solutions are only for those with the cold low and flat fields, he says, and refers to the pollution. Obviously you pollute when you burn oil or any other combustible liquids no matter if it is in a can or the specially developped

chaufferettes.

Constant irrigationThe third weapon against the frost is to install a real sprinkler system. The principle is during the frost period constantly to irrigate the buds with water. This prevents their temperature in dropping under zero. The system is very effective, but it does use 50 cubic metres of water per hectare per hour. On top of that you must monitor it very often. A sprinkler can fall over, and should this happen, the wet buds will be utterly lost in the frost.

Irrigation, lamps, mills... or simply nothing. The critical period normally only endures very few days. In 2001 the champagnehouse Moët et Chandon irrigated their endangered parcels two nights, when the temperature fell to minus 4,5 degrees Celsius. Almost 20 years before that, they had to irrigate six nights. With the general warmer climate the inventive antifrostmethods have become less crucial for many. Also the reserves of wine, that you may use if necessary and if permitted - like in 2003 - instead of the wine of the year - have made the winegrowers much less dependant on their entire harvest.

However not more independant than the fact that widespread frost in 2004 could have meant economical problems, because the reserves were almost empty. Maybe this is why some winegrowers keep a good grip on their little lamps and electrical airscrews.

På dansk The cans spread out through the rows with few metres between them.

The cans spread out through the rows with few metres between them.